Credit: Ernesto del Aguila III, NHGRI

Few 20th century achievements portend more promise than the digitalization of biology, made possible by the Human Genome Project and a whirlwind of subsequent advances. The omics revolution continues to develop and mature rapidly as sequencing becomes cheaper and easier for individual scientists from just about any discipline to do in their own labs in an automated fashion. Data science, now a necessity for almost all biomedical research, is thus the perfect place for the infusion of new talent, new perspectives, and different ways of thinking. It is thus also a great place for us to concentrate effort on integrating scientific workforce diversity with data science. I believe the ensuing opportunities, technology advances, and health benefits will materialize quickly.

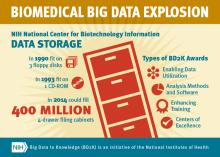

My arrival at NIH in 2014 arose from recognition by the NIH Advisory Committee to the NIH Director that diversity is so integral to modern biomedical inquiry that strategic leadership and coordination is vital. Clearly, the same could be said for data science. Established in 2013, Big Data to Knowledge (BD2K) is a trans-NIH effort to “enable biomedical research as a digital research enterprise.” Its goals are to help researchers find meaning in vast amounts of DNA and other molecular data. This is really needed because data-science research is no longer the domain of genomicists and bioinformaticists. Rather, it is integral to the research all of us do. It is part of modern biomedical research.

A new BD2K partnership program with minority-serving institutions directly addresses barriers to recruitment and retention of individuals from underrepresented groups.

My own research is a case in point. I came to data science unexpectedly, through the lens of an extraordinary scientific opportunity. While a research cardiologist at Stanford, studying causes and treatment of heart-transplant rejection, I had an aha moment, after hearing about research from a scientist in the next building over. He, Steve Quake (and still my collaborator many years later) had reported the ability to detect fetal DNA in blood samples from pregnant women, use high-throughput methods to sequence that DNA, and to detect circulating fragments of DNA that provide evidence of birth defects like trisomy 21, which causes Down syndrome. I reached out to him and we both realized the same thing:

“An organ transplant is essentially a genome transplant!”

The presence of donor DNA (green) in a blood sample of a heart-transplant recipient enables early detection of organ rejection.

When a heart-transplant recipient receives a donor organ from another person, they inherit that person’s DNA that is integral to the donor heart. We have discovered since then that we can detect early signs of rejection of a donated heart or lung based on leakage of the organ’s DNA into the transplant-recipient’s blood. This has incredible promise for improving patient outcomes, including reducing health disparities. In fact, my current research is investigating racial differences in transplant-recipient outcomes. We have teamed with transplant centers in the D.C. Metro area that have high proportions of African-American/Black transplant patients. They are known to have poorer outcomes compared to whites, and now we are searching their genomic DNA for reasons why and how to improve their prognosis.

That initial encounter with data science was a transformative moment for my research, which has taken exciting new directions based on this collaboration. As a physician scientist, I have become reasonably conversant in data science, but we need many more people, from a diversity of backgrounds and areas of scientific interest who speak this language and can translate it to others. The need is immense.

According to a 2011 report from the McKinsey Global Institute, data science, or Big Data, is the next frontier for innovation and productivity in many sectors of our economy, including science. The impending barrier to progress? A talent shortage in which skills not previously taught to scientists are key: managing enormous data sets, developing new analytical techniques individualized to project needs, statistical innovations, and machine learning. Like scientific workforce diversity, achieving necessary gains in the talent pool will require proactive thinking and action, and drawing from our nation’s entire intellectual capital.

SWD and data-science training have a perfect opportunity to join forces toward a common goal. In a similar partnership model, NIH’s Diversity Program Consortium (DPC), which I described in a previous blog, my office teamed with NIH colleagues to enrich the BD2K initiative by requesting applications for the Enhancing Diversity in Biomedical Data Sciences Grant. This effort encourages collaboration between minority-serving institutions and NIH BD2K Centers of Excellence. Through this partnership, four institutions now receive BD2K funding: California State University, Fullerton; California State University, Monterey Bay; Fisk University; and the University of Puerto Rico, Río Piedras Campus. Similar to the NIH-funded DPC BUILD program, the BD2K partnerships directly address barriers to recruitment and retention of individuals from underrepresented groups: providing research experiences, funding curriculum development, and developing mentoring relationships. We anticipate this collaboration to enhance diversity of the data-science talent pool, since collectively, the four funded minority-serving institutions serve nearly triple the proportion of Hispanic, Asian/Pacific Islander, and African American students compared with national enrollment rates. While this program represents a good start, clearly it will require expansion to ensure a rapid and sustained impact.

As I’ve noted in a previous blog, sustaining scientific workforce diversity hinges on focusing on career transitions, where young scientists have to make choice: “Do I want to stay on this path? What’s in it for me?” As with other STEM disciplines, the fledgling data-science researcher population does not reflect the diversity of the United States. We know that the gap arises from many factors, including financial pressures, stereotype threat, institutional biases in recruitment, and lack of mentoring about skills and opportunities from Big Data practitioners.

Students in the Graduate Summer Opportunity to Advance Research Program (GSOAR) pose for a group photo with NIH Office of Intramural Training and Education (OITE) staff.

Credit: Ulli Klenke

In 2016, my office partnered with the NIH Office of Intramural Training and Education (OITE) to launch the Graduate Summer Opportunity to Advance Research Program (GSOAR). The NIH GSOAR Program is an intensive summer research experience for early-stage biomedical graduate students from any discipline aimed at developing communication, critical thinking, career readiness, and leadership skills needed to succeed in graduate school and beyond. The summer 2016 inaugural class was highly diverse (participating students were 44% African-American/Black, 6% Hispanic, 11% Asian, 6% American Indian/Alaska Native, and 33% White). GSOAR puts a special focus on resiliency to equip participating students with skills and knowledge needed to persist in science. Another key focus, of relevance to this blog, is a data-science boot camp – providing participants a head start on gaining critical quantitative skills.

Finally, another key opportunity is using the power of data science to enrich scientific workforce diversity, as I mentioned in my last blog: “Why not harness tech tools and expertise to develop tools to recruit and retain diverse talent?” I am optimistic that data science can help people find new team members through advanced search algorithms that enable scientists to veer outside relatively closed collaborative networks. Some tools are available online, such as those that aim to forge team-science collaborations based on shared scientific interests. Making these connections is likely to have important effects on individuals from underrepresented groups, whose professional/co-author networks are often less expansive than those of researchers from majority groups. Lack of access to key research networks can have a negative impact on career advancement.

What actions are needed on the part of institutional leadership to ensure we bring diverse talent into data science? Key strategies include broadening diversity among trainees; using systematic approaches to identify a diverse pool of highly trained individuals; instituting proactive outreach strategies for diverse talent; and creating inclusive institutional environments and cultures. Institutional transformation toward excellence in data-science inclusion will require that we address some deep questions. Is our culture welcoming to all types of scientists? Can a woman or a person from an underrepresented group climb the academic ladder of data science, and if not, why not?

Albert Einstein’s words stand the test of time: “We cannot solve our problems with the same thinking we used when we created them.”

This is certainly true for efforts to enhance diversity in existing fields where change requires shifting cultural norms at the institutional level. Data science being in the process of its earliest development offers a unique opportunity to use new kinds of thinking from the get-go, to engineer a field that values diversity of its workforce as an essential element for success.

Data science: Meet diversity. It’s a win-win.